Supporting artists

Angalia solely showcases the work of artists from the Democratic Republic of the Congo (DRC). We have specialized in the DRC because of our particular interest in this country, whose artistic dynamism is fascinating and also because truly supporting the artists requires us to build a close relationship with them. The gallery’s director, Pierre Daubert, travels to Kinshasa three times a year.

Being an artist in a country like the DRC, which is struggling to recover from a long crisis, is a daily challenge. And in this context, being a gallery owner means going above and beyond the classic representative role. The artists must be given all kinds of support, depending on their individual situation, starting with the security offered by a long-term link. Angalia and other stakeholders do just that.

Forging

long-term links

A partnership in DR Congo with Texaf-Bilembo

Development

via a local partnership

Angalia’s foothold in Kinshasa has been strengthened since 2014 by a partnership with Texaf-Bilembo Cultural Centre (texaf-bilembo.com) run by Chantal Tombu and Christine Decelle. Angalia regularly exhibits the work of the gallery’s artists in solo exhibitions with catalogues at the cultural centre, thus helping to raise the profile of the artists both in the DRC and in Europe.

Art in the DRC

The dynamism and vibrancy of the DRC’s art scene are nothing new. Big names, with Chéri Samba at the forefront, are now firm favourites in private and public art collections and the art market. The Fondation Cartier’s stunning retrospective of 80 years of art in the DRC held in 2015 (Beauté Congo, Congo Kitoko 1926-2015) the exhibition Art/Afriques, le nouvel atelier at the Fondation Louis Vuitton in 2017, Kinshasa Chroniques at the Museum of French Monuments in 2020, and the success of System K, a documentary by Renaud Barret about the vibrant street art scene in Kinshasa, all bear witness to it.

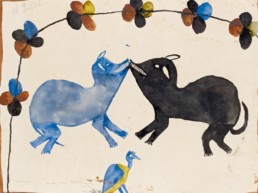

But let’s quickly go back to the origins of the DR Congo art scene. Modern art in the DRC first emerged in the 1930s, in what was then the Belgian Congo. Supported by a Belgian patron Georges Thiry, Lubaki and Djilatendo stood out from the crowd with touchingly simple works on paper.

The Atelier du Hangar developed in 1946 in Lubumbashi at Pierre Romain-Desfossés’s instigation. Artists such as Pilipili, Bela and Mwenze were figureheads for the school. Unlike their predecessors, they experienced a certain amount of success abroad, even having their works exhibited in the US.

The Kinshasa School of Fine Arts was founded in 1943, firstly taking the form of a school, before gaining its definitive name in 1957. Nowadays, the academy teaches visual art (ceramics, beaten metalwork, painting and sculpture) and graphic arts (interior design and visual communication).

During the post-colonial period – a complex time in more than one respect – contemporary art was caught in a stranglehold between attempts to take ownership of western concepts, which were widely challenged, and the assertion of a brand of African art tinged with nationalism and lacking in inventiveness.

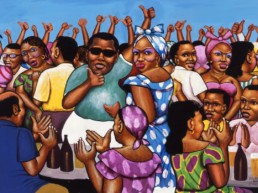

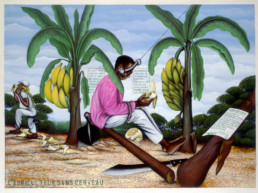

However, a movement – popular painting – did emerge. The movement was established in the first instance by the Art partout exhibition in Kinshasa in 1978. Chéri Samba defined popular art as follows, “It’s an art form that comes from the people and is for the people.” Apart from Chéri Samba, key members of the movement are Moke, Chéri Chérin, Pierre Bodo and JP Mika, who all learned their trade painting advertising boards, as they started out painting shop fronts, in bars, hairdressers and so on, in order to earn their living.

Once on canvas, this art, which borrows some of the formal characteristics of cartoons, began to tell the tale of street life, romantic and social mores, and finally everything that happens in the city. It sometimes goes beyond these themes, as international politics were also caricatured.

In the 1980s, model makers unexpectedly proved to be the most creative artists, with their ranks including Bodys Isek Kingelez, an architect and model maker who creates visionary models of modern cities, and Rigobert Nimi; they have now achieved international recognition.

The liberalisation of the 1990s was chaotic and was followed by a serious crisis, yet it did open the way to all sorts of artistic experiments. Some sought to be anti-academic (Francis Mampuya), while others drew on an education in the DRC and abroad (including Strasbourg School of Fine Arts). True diversity gradually took hold.

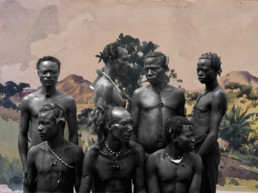

With his famous cartridge cases, Freddy Tsimba revolutionized Congolese sculpture, mixed techniques gained a foothold (Aimé Mpane, Kura Shomali, Steve Bandoma and Vitshois Mwilambwe), photography, which until then had been less prominent, apart from Jean Depara, has become established with Sammy Baloji, acclaimed for his work on DRC’s history and memory, Kiripi Katembo, focusing on urban change, and more recently Gosette Lubondo, who explores the memory of abandoned places; and drawing, which is also developing very well, driven forward by numerous talented cartoonists, as well as artists such as Tsham, Mega Mingiedi, and Houston Maludi. Painting retained a very important place, largely due to the international success of Chéri Samba, as well as JP Mika and Eddy Kamuanga, and the development of the famous Pigozzi collection, giving the major artists both economic and artistic support over a period of around 15 years.

Nowadays, this colourful community of artists is well represented in the venues where African art is exhibited, making the DRC a leading country for African contemporary art.